How sustainability races have been bringing the energy-efficient car of the future closer for 40 years

Two alumni see the development of their own vehicle as the highlight of their student time.

On behalf of TU/e, Henk Heijnen (65) and Martijn Lammers (33) have both won a design competition for a more fuel-efficient road vehicle: Heijnen in 1979, Lammers in 2015. The one is free-thinking, the other is driven, but both have their own view on the sustainable developments taking place in the mobility sector. TU/e brought them together for a discussion on, among other things, the usefulness of sustainability races for an energy-efficient automotive industry.

POWER TO THE PIONEERS

TU/e is celebrating its 65th anniversary, which is why in this lustrum year we are making a link between the past, the present and the future. In a series of double interviews we bring together pioneers from the past and present; pioneers who may have grown up in a different era, but who do share a common passion for a particular discipline. How do they view the (scientific) developments of then and now? What are the similarities and what are the differences? Part 1 focuses on sustainable mobility.

Even winners suffer setbacks from time to time.

Henk Heijnen laughs as the anecdotes drift across the table this afternoon in the Atlas Building. He recalls that particular Saturday in June 1979. Heijnen was participating with a team of twelve in a design competition initiated by Shell for fuel-efficient vehicles. Universities from all over the country had gathered that morning on the campus of the Twente University of Applied Sciences in Drienerloo. Until a few hours before the start, Heijnen had no idea that he would eventually end up behind the steering wheel of their lightweight tricycle.

"After a final practice lap, our driver Jac Riemens said the engine was not working properly," recalls Heijnen, who at the time was studying at the Department of Mechanical Engineering. What was the problem? It turned out that Riemens was having trouble with controlled acceleration. More precisely because the team had calculated that for optimal efficiency, the driver should accelerate for four seconds and then let the vehicle turn over for forty seconds. With the carburetor being so precision-tuned, this meant that too much pressure on the throttle caused the engine to stutter.

Heijnen knew the engine inside out. "The combination of that knowledge and undoubtedly my slightly dominant nature ensured that I was assigned as the driver just before the start, even though I wasn't exactly the lightest of the group. It was Godsent chance. I have never seen Professor Wim Koumans so nervous."

Box for bombs

"Not everything went smoothly for us either," Martijn Lammers points out. In 2015, he was part of Solar Team Eindhoven that won the World Solar Challenge in Australia with the Stella Lux - the solar car on display in the Atlas Building. He remembers how his team received a phone call two years before, just prior to the start of the competition, from the airline that was to transport the solar car to the other side of the world. The pilot refused to take the car's lithium battery on board. There had previously been problems with lithium batteries in telephones spontaneously catching fire during a flight.

Lammers: "Well, what do you do then? We considered all kinds of things." The solution? A matter of logical thinking, nods Lammers. "After all, dangerous objects often have to be transported by plane." So the Solar Team contacted the ministry of defense. No stranger to the student team, because the defense site in Oirschot is regularly used as a test site for the solar car. "We then arranged for a crate in which bombs are normally transported," says the team's spokesman. This way the battery could still reach its destination on time.

Great supremacy

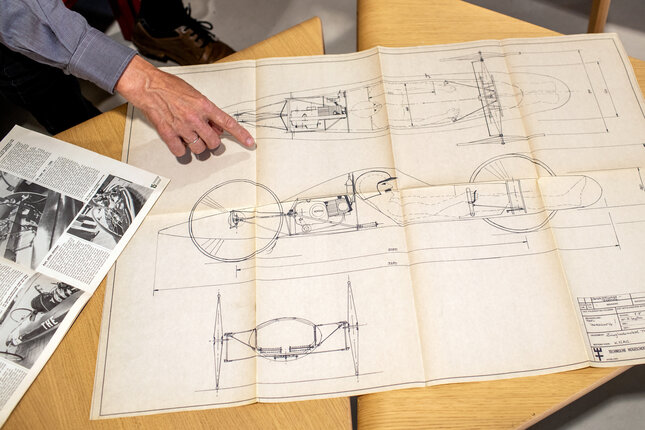

The performance of both men and their teams did not suffer from these vicissitudes. Heijnen and his team won the race in Twente by a large margin; they even broke a world fuel economy record. The car - jokingly referred to by Heijnen as "a canoe driving on bicycle wheels" - drove over 731 kilometers on a single liter of gasoline. Heijnen: "Not that we actually covered that distance. We drove for about two hours and it turned out to have used 18 cc of fuel. The math was done on that basis."

TU Delft came up with an ingenious car, but did not make it to the finish because the engine stalled after the supply of fuel had been exhausted prematurely. Heijnen: "Of course, we thought that was hilarious, there was already a healthy rivalry between Eindhoven and Delft at the time."

More than 35 years later, Lammers and his Team Solar may have finished second in the World Solar Challenge, but in the Cruiser class for energy consumption, the number of passengers carried and practical properties play a more important role. That's why the jury crowned the Stella Lux as the winner. Lammers: "We did not have the most aerodynamic car, nor the lightest and not the most optimal for solar panels. But it was the way we combined those factors that made our car a winner. Not leaning too heavily on speed, efficiency or practicality, but rather learning to compromise." Then, laughing: "Poldering. Something we Dutch are good at."

Working Pragmatically

What was the strength of the Heijnen team? The pragmatic way of working. After all, the team is split into a vehicle and an engine team. For the engine, a special simulator set-up was built in the laboratory so that the two teams could work simultaneously and not be dependent on the other. The cooperation with the professors and staff at TU/e was also very pleasing: "As students, we really had the feeling that we were doing it ourselves."

Lammers: "I recognize that. We even had our own building as a student team. Many of the professors involved weren't sure if we were going to succeed, but we could always ask for advice and we were given the freedom and space. And, of course, everyone was very proud afterwards. There is a lot involved in a project like this. It's not just building the car, but also project management, communication, logistics and planning. We had never done all that before. And it's really nice to work with students from different departments."

Heijnen: "It was the best time of my student life. I made friends for life from it."

Lammers: "I certainly agree with that. And I dare say I learned more during that period than I did during my years in the lecture rooms."

Oil and climate crisis

The reason for Shell's design competition, now more than forty years old, was the oil crisis of 1973. Heijnen: "The production of oil was drastically reduced at that time, which caused prices to skyrocket. It was a wake-up call for everyone. This had to change, we all thought. More fuel-efficient above all."

Lammers: "Was social urgency the reason you entered the contest?"

Heijnen: "Several factors played a role. Social urgency played a role, but to be honest I found it really fun to participate in such a competition with a club of young people. I'm not a hardcore environmental freak, I have petrol in my blood. Besides, these were different times. A good example of change is the CO2 issue: the role of CO2 in global warming was not so clear back then."

Lammers: "I understand that. I grew up in a different era, in the middle of the climate crisis. Our participation in the World Solar Challenge was partly inspired by ideology. Making the mobility sector sustainable is a slow process. A bit more economical, a bit better, but not fast enough, we thought. Things could be done differently. And of course it was a great challenge to develop something that resembles a real, practicable car."

Heijnen: "Nevertheless, the oil crisis did contribute to the development of more energy-efficient cars. Worldwide, stricter requirements for engines came quickly after that."

Lammers: "With five members of the Solar team, we founded Lightyear in 2016. The Lightyear One is more than a car, it's a statement. With it we show everyone that it can be done: a car powered by solar cells that is not dependent on charging stations and can charge itself via solar cells. After the World Solar Challenge we were praised for our innovative ideas. We expected the automotive industry to pick it up, but it didn't happen. That's when we started doing it ourselves. The car industry is sometimes still stuck in habitual frames of mind, although they are interested in the decisions we make."

Heijnen: "This is where I have stand up for today’s automotive industry. We are all used to cars that are extremely reliable. Just think about it: if you build 100,000 cars and one of them has serious defects, you're not doing well as a car manufacturer. Bit 1 in 100,000, that's not much. For a car to be so reliable you can’t allow much leeway. So when you start something new, you have to be very sure of yourself."

Lammers: "That is indeed an advantage for us. As a young company you can start with low volumes and first get all the teething problems out of your vehicle. That way you can grow into the industry step by step."

Heijnen: "By the way, I had never expected that electric mobility would take off like this now."

Lammers: "Didn't it used to be about electric driving?"

Heijnen: "It certainly did. The funny thing is that a professor, whose name I can’t recall, used to say: 'electric mobility is the future, remains the future and will always be the future'. In short, the tenor was that an electric breakthrough would not come. So that was a view, with the knowledge of the time, with which I could agree."

Lammers: "It's been going fast the last few years."

Heijnen: "The hybrid car was the perfect intermediate step and served as a springboard. When I graduated, they were already busy converting conventional cars to electric vehicles at the TU/e transport engineering lab. Batteries were big in the 1980s and recharging took a long time. That's why they were thinking of package swaps; battery packages that you could replace at a gas station the moment the battery was empty."

Lammers: "That is remarkable, because it was only around 2010 that a company called Better Place saw a working business model in interchangeable batteries. While that company didn't make it, it's still remarkable that research was being done into this as far back as the 1980s. People misjudge that long lead time."

Heijnen: "It is an evolutionary process, where new solutions are not only important in the mobility sector, but also in other sectors. The fact that batteries are now lighter and faster to charge is mainly related to innovation in the electronics and energy sectors."

Fuel engines completely replaced

Both are unanimous about the near future, in which electric transport will completely replace the current fuel engines. Lammers: "I am aiming for vehicles, such as the Lightyear car, that are not dependent on the electricity grid. After all, you already hear about the danger of the electricity grid becoming overloaded. Moreover, in the future we will be sharing the car a lot more, especially in the city where you will see fewer and fewer cars."

Heijnen: "My feeling is that these developments will happen faster than you think. My youngest son, who is 30 years old, lives in London and in his circle of friends nobody has a car. What do you need a car for in London? Besides, I don't think we can yet imagine the systems we'll be using in fifty years."

Lammers: "Research is being conducted into nuclear fusion in Eindhoven. If that continues to develop, everything in the field of energy will be completely different."

Appealing challenges

After almost two hours the conversation comes to a close. Other mobility competitions were also discussed, such as the Shell Eco-marathon in which Heijnen took part, including one on the famous Hockenheim circuit. There, he remembers, a Swiss team made a nasty mistake. "They were cheating by using fuel from the float chamber instead of from their own tanks. They had just been a little too fanatical, because they came back with more fuel than when they left," laughs Heijnen. The Swiss were logically disqualified.

The enthusiasm with which both Lammers and Heijnen recounted their participation in the aforementioned competitions raises the question of whether this type of initiative should not be organized more often. Both nod in agreement.

Heijnen: "Indeed, more challenges like this should be organized, where youngsters can roll up their sleeves and work on appealing challenges, preferably in competition."

Lammers: "Then the applications of technology also become a lot more concrete. People can then form an image of what you learn at a technology university. It helps make the technology more attractive."

Heijnen: "And that in turn leads to a greater influx of students at TU/e." With a wink: "So maybe TU/e itself can organize these kinds of challenges or competitions? In any case, I enjoyed it immensely at the time!"

Latest news