‘It's only when students work with the material that it sticks’

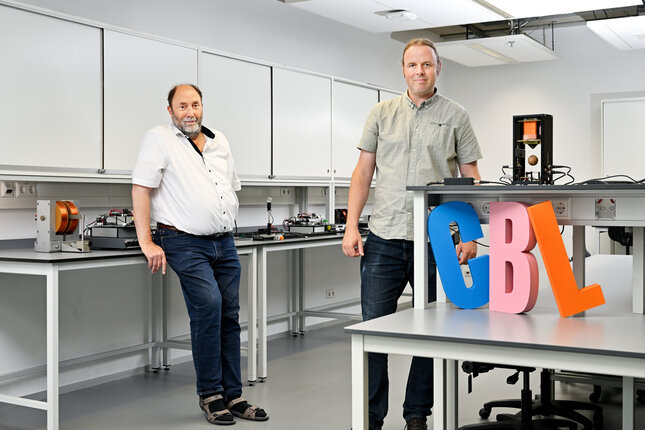

The Faces of Challenge-Based Learning series: early adopters Gerrit Kroesen and Rudie Kunnen of Applied Physics and Science Education redesigned a course to incorporate CBL seven years ago.

![[Translate to English:] Gerrit Kroesen (left) and Rudie Kunnen. Photo: Bart van Overbeeke](https://assets.w3.tue.nl/w/fileadmin/_processed_/2/9/csm_BvOF%202023_0714_ABR%20-%20CBL%20-%20Gerrit%20Kroesen%20_%20Rudie%20Kunnen_91aa1aa059.jpg)

With the innovative educational concept of Challenge-Based Learning (CBL), we are training the engineers of the future at TU/e. Starting this academic year, CBL will play a larger role in the curricula of all our bachelor's programs. Through a series of stories, we give a face to the form of education that sometimes takes students - and teachers - out of their comfort zone, but above all prepares them for the challenges they will tackle as engineers. In this episode we meet Gerrit Kroesen and Rudie Kunnen. They were among the first lecturers to convert a course to Challenge-Based Learning.

Seven years ago when they were faced with a failing course, they had no plan at the ready to redesign it as a Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) experience. Yet this is what happened, over time, when Gerrit Kroesen and Rudie Kunnen took on the second-year course Control Engineering. “Had this technical element in the curriculum been lost, we would have regretted it,” says Kroesen.

And so they became some of the first lecturers to embrace this new teaching and learning style. “We weren't just giving CBL a whirl. We wanted the students to clearly remember what they had learned and were looking for an educational approach that would achieve this. It wasn't about the approach, the approach simply had to do the job,” says Kroesen, professor and former dean of the Department of Applied Physics and Science Education (APSE).

What is Challenge-Based Learning?

In this innovative educational concept, students work together to experience how their discipline can contribute to solving challenges from the world around us. They learn what knowledge and expertise is needed to do so and can immediately apply and deepen the knowledge they have acquired in practice by studying or doing research.

Together with students from other disciplines, as well as stakeholders from business, government or science, students learn to think at the system level. In the process, they also learn various other competencies such as collaboration, communication, planning and organizing.

From DBL to CBL

Their first step was to convert the classically taught course into a DBL course (Design-Based Learning). “We poured disciplinary knowledge from control engineering into a DBL mould. DBL, which has students working in groups to produce a design, was often detached from the theory, and transferring required knowledge wasn't part of its remit. But from the get-go we embedded knowledge transfer. We were the first teachers to do so. That's why Lex Lemmens, the former dean of the Bachelor College, called us the godfathers of CBL,” says Kroesen with a smile.

While the course didn't check all the CBL boxes, it had all the main ingredients - with the exception of multidisciplinarity, missing because the cohort included only APSE students. The assignment was open-ended and no one was telling the students what to do. They had to plan, communicate and cooperate in the broadest sense. And, where the course really differed from DBL: the theory was no longer taught in lectures.

D-I-Y

“Working with their group, students have to work out for themselves what theory they need to know in order to successfully complete the assignment,” says Kroesen. One of the assignments for the second-years was to get a small ball to hover in the air. They were given a magnetic coil, a circuit board, some power plugs, cables and a small metal ball.

“Of course we pointed them in the direction of reading materials, and there's plenty of stuff about control engineering on YouTube. And there were guest lectures to help get them started. Still, the students were casting around for a starting point,” says Kunnen, associate professor at APSE.

Students had to get used to the new way of working that requires them to apply the theory of control engineering to build something. “It's not about knowing something off by heart, but about understanding and the ability to apply knowledge; a skill they'll also need at work. You have to get them working with the material, only then does it stick,” says Kroesen.

Initially, I felt pretty guilty about abandoning students to their fate.

Professor Gerrit Kroesen (APSE)

For the lecturers, too, it was quite a challenge - jettisoning the classical method involving lectures and instructions. “In the early days of this course we used to sit in my office and wait for someone to come in with a question. I used to feel pretty guilty sometimes that we were abandoning them to their fate,” recalls Kroesen.

Dropping in to see Kroesen and Kunnen in their offices proved too great a hurdle for students. In the next round the lecturers made sure to sit among the groups of students, taking on a guidance role as the students worked in the TU/e innovation Space in Matrix. Now they were very approachable if a student had a question.

Awfully remote

“A lecture feels awfully remote; no one dares ask a question in front of a room full of faces and hardly anyone comes to the instruction session,” says Kunnen. “Now, instead of that, all the students are present, the lecturer walks around and is on hand to answer questions, or might even speak with groups. You are much more closely involved.”

Another advantage is the social control within the groups. “If someone leaves early, the group's achievement suffers. They learn to speak up when someone's going through a lazy phase - although that's never easy. But what I really value is that they learn from each other, spark ideas off each other and influence each other,” says Kroesen.

Above all, students must learn from each other.

Professor Gerrit Kroesen (APSE)

But learning the necessary disciplinary knowledge, that's still a challenge, Kunnen believes. “How can you guarantee that every student will acquire the necessary theory?” They noticed a division of tasks occurring naturally within their groups: one person will be good at theory and will take care of that; another will be handy with MatLab; and someone else will do the presentations.

“There were always two students who had really studied the theory. That's why Rudie came up with the idea of testing the theory with a digital exam,” says Kroesen. “After that they are free to specialize in whatever task they most enjoy,” adds Kunnen.

To measure is to know

After running the course in this way for three years, Kroesen started gathering metrics to see whether the new method was working. “I asked three 'generations' of students to come back and take a 30-minute practice exam comprising open questions. One group had taken the old DBL-style course, one had taken the new-style course, and one had taken the new-style course and sat the digital exam.

“Between the old and new methods there was a full grade's difference in the scores,” says Kroesen. “And the group with the added digital exam showed a further improvement. Nothing spectacular, but certainly noticeable. So it does have an effect,” Kroesen concludes.

Better scores

He adds with satisfaction that retention of the course content is considerably better among those students who experienced the CBL approach. “When you get students working with the material, it sticks much better. This is what motivates us to use Challenge-Based Learning as an educational approach.”

You need to do what you're good at, and work with others who bring their own expert knowledge.

Professor Gerrit Kroesen (APSE)

Together with educationalist Sonia Gómez Puente, Kroesen wrote a paper on the research. “Co-production, that's the way you need to design your education,” he says with conviction. “All of us science nerds want to provide the best education and transfer our knowledge in a way that makes the students both want to receive it and able to remember it. To find out how best to do that, you need to work with an educationalist. They are the experts.”

Experts

“I'm doing the same in my research,” Kroesen says, and by way of illustration: “When we're looking at medical applications for plasma, I don't play the physician. Other people are better at that. You need to do what you're good at, and work with others who bring a mastery of the other piece of the puzzle.”

Enjoy, but drink in moderation. It applies equally to CBL.

Associate Professor Rudie Kunnen (APSE)

Despite being pioneers in CBL, Kunnen and Kroesen remain critical. “Enjoy, but drink in moderation. It's a rule that applies equally to CBL,” Kunnen is keen to emphasize. “For many subjects, this educational approach is a very good fit. But not all. So don't go forcing its adoption across the board.”

“It varies from program to program,” adds Kroesen. “At Mechanical Engineering and Biomedical Engineering the curricula are better suited to CBL. Their disciplines are much more applied than those in theoretical physics. By its very nature, Mechanical Engineering (ME) is multidisciplinary. It requires physics and math.”

Future

At the end of the coming academic year Control Engineering will be renamed Control of a Flexible Robot System and delivered as a joint course for second-year bachelor's students at the departments of APSE and ME. “The course they were giving at ME was similar to ours in terms of content. The idea of combining them came up,” says Kunnen.

And so the course will become multidisciplinary and more open-ended. “We'll be working with a setup involving a robotic arm and a web cam. The students will have free rein to think up cases with industry relevance, for example in the area of quality control on a production line,” says Kunnen.

Growth

With the merger comes a challenge: the number of students will nudge the five, six hundred mark, compared to the 150 or so taking the course at APSE. In this scenario, master's students of Mechanical Engineering will take over the supervision of the student groups, a role involving a lot of contact with the students. “They have a broader background in control engineering than our students,” says Kunnen.

“I think the staff at ME have come up with an elegant solution: they have a master's course on which credits can be earned for supervising bachelor's courses. Solutions like this are needed if you want to introduce more CBL across your programs,” says Kroesen.

As a lecturer you're no longer coaching students, you're coaching their supervisors.

Associate Professor Rudie Kunnen (APSE)

“The lecturer's role changes as the groups get larger. You're no longer coaching the students, you're coaching the supervisors of the students. That's a shame, but it's an inevitable consequence of scaling up,” says Kunnen.

Challenges on the factory floor

In an earlier pilot, five small groups of students worked on open-ended challenges set by stakeholders drawn from industry, says Kunnen. “When it's just a handful of groups, it's manageable for companies. They can send someone along to explain the kind of problems they are having on the factory floor. It would be difficult for companies to closely supervise hundreds of groups. They'd be so busy they'd have to shut up shop,” he says with a wink.

“But students really appreciate these external stakeholders, so we'll have to find a happy medium. It's much more fun solving a real problem.”

With CBL there's no distance between the lecturer and the student. That's a nice side effect.

Professor Gerrit Kroesen (APSE)

“As a lecturer involved in this educational approach you're very close to the student,” says Kroesen. “Students sometimes come up to me in the corridor and ask a question. It's a nice side effect of CBL, this informal interaction. I have the impression the students feel the same way. It makes CBL a very rewarding way of delivering education.”

MORE FACES OF CHALLENGE-BASED LEARNING

More on our strategy