ICMS: the institute that revolves around people

The place where interdisciplinary collaboration has been stimulated for 15 years.

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://assets.w3.tue.nl/w/fileadmin/_processed_/6/b/csm_Jan_van_Hest___Bert_Meijer_door%20Bart%20van%20Overbeeke_7090cd5630.jpg)

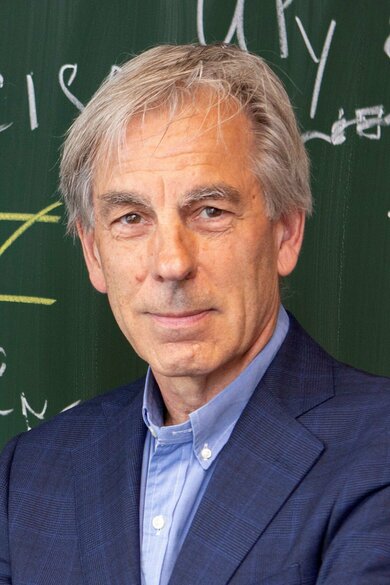

The Institute for Complex Molecular Systems (ICMS) is celebrating its 15th anniversary during the Annual Symposium on March 30 and 31. Much has changed over the years; for the last five years, the institute has had a new scientific director, the research field has broadened and the areas of expertise have been redefined. But the most important thing has stayed the same; it is still the place where interdisciplinary cooperation is stimulated and where people come first. Former scientific director Bert Meijer and his successor Jan van Hest look back on the institute’s 15-year history.

When the institute celebrated its tenth anniversary five years ago, its founder and then scientific director Bert Meijer felt the time was right to hand over the baton to a successor. For his former “pupil” Jan van Hest, who was given the honor to take over, this was one of the reasons to return to Eindhoven at the time. “I had always been drawn to the spirit and quality of the ICMS, so it was a great honor to take over the directorship,” says Van Hest. “But also a great responsibility, because ten years of work had gone into the institute and of course you want to see to it that the level of excellence is maintained.”

Blueprint

What did the past five years under his leadership look like? “The research field has become even broader than it already was; new research areas were added,” says Van Hest. “One thing that’s really nice is that TU/e has embraced ICMS as a model for interdepartmental cooperation,” he continues. The three institutes founded in the past few years - the energy institute EIRES, the artificial intelligence institute EAISI and the photonics institute Hendrik Casimir - were all inspired by their successful predecessor. “Their structures and activities are largely based on what we do here; we serve as a blueprint for other institutes,” says Van Hest. “The fact that they’re following our example shows that the university values our work and that the institute is genuinely succeeding in bringing people together and advancing research.”

Similarly, the ICMS was following a successful example itself 15 years ago; the American Materials Research Lab (MRL) at the University of California in Santa Barbara served as a role model for the institute at the time. Instead of having just one large natural sciences department, many American universities have multiple smaller ones - just like TU/e. Six of these smaller departments were brought together in a single organization: MRL, thus enabling interdisciplinary cooperation.

With the same goal in mind, Meijer and his fellow professors Mark Peletier, Rutger van Santen and Jaap Schouten initiated the establishment of a new institute in 2008. Its purpose was to bring together scientists and different disciplines from the five cooperating departments: Mathematics and Computer Science, Biomedical Engineering, Applied Physics, Mechanical Engineering and Chemical Engineering. Ever since, the ICMS has been a place where scientific collaboration between different disciplines is stimulated. The focus of the research is on the study of molecular systems, both at the fundamental and application levels. “Molecules play a central role in this and you need a lot of different disciplines to advance the field,” says Van Hest.

Which colleagues and disciplines you need to join forces with to move forward can change over the years due to new developments. “For example, when we started out 15 years ago, artificial intelligence was a non-existent area at our institute,” says Meijer. “Those are important new research areas you have to be involved in.” The research field is very dynamic, which means there are constantly shifts like these. “You have to keep asking yourself if the collaboration is still paying off. If that’s no longer the case, you have to be able to change it,” says Meijer.

Living room concept

Since 2012, the Ceres building has been the beating heart of the ICMS. This is the facility that houses the institute, which had to make do with the basement of the Main Building (now Atlas) in its early years. It was created by refurbishing the old boiler house. According to Meijer, Sagitta Peters, the then business manager, played an important role in the project. “She was very involved in the refurbishing and spent a lot of time working with an architect. Among other things, that’s how the idea of the big, open windows came about, which allow you to see everything.” Not only Meijer and his team were happy with their new home; in 2013, Ceres was named Building of the Year.

"Ceres is a place where you can bring people together in a very informal and approachable way."

The building has an important function; it serves as a central place where people come together. “It’s sort of like a living room concept, a place where you can bring people together in a very informal and approachable way,” says Van Hest. “With a small but dedicated team, we organize all kinds of lectures and activities so that people can meet. This results in long-term collaborations, which is incredibly important,” he stresses.

Nothing is obligatory

Not every collaboration bears fruit; Van Hest knows that better than anyone. “Sometimes you bring people together for a certain project only to find out that it’s not a good match. In that case, the group may decide to move on to other things after a while.” According to him, this freedom is precisely what makes this form of collaboration so valuable. “Not everything works out, but at least you tried.”

Meijer nods in agreement: “Nothing is obligatory. That’s been our motto from day one. If you organize something and nobody shows up, you did something wrong. It also keeps you alert because you have to ask yourself: what subjects are exciting, what would people be interested in?” And once the enthusiasm wears off, you should stop, Meijer believes.

Interfaces

It almost sounds like this form of interdisciplinary cooperation only offers advantages. Still, 15 years ago, not everyone was as excited about the idea. “Some people used to think: we could do that within the department too,” says Meijer.

"The most important new advances are made at the interfaces between different disciplines."

“People couldn’t see it back then - and sometimes they still don’t - but the most important new advances are made at the interfaces between different disciplines,” says Meijer. The interface between two departments is an exciting place where many new developments can occur, but it’s sometimes difficult for researchers to explore this area. “If you do, you're not at the “core” of your own department and you can feel a bit left out,” Meijer explains. According to him, ICMS is the right place for those who do not completely fit in. “Here, you’re given that space and you actually strengthen each other.”

Initially, the institute had three lines of research; now there are seven focus areas, including materials for regenerative medicine or polymer technology. “Our new strategy will change that,” Van Hest says. The ICMS has grown in recent years and the research field has broadened. Van Hest noticed that it was sometimes difficult to explain the research areas. “It was too complex and you have to make it simpler. That’s why we decided to go back to just three domains.” The first domain focuses on how molecular systems are put together, the aim being to gain a better understanding of them. Then there are two application areas dedicated to advanced materials and life sciences. “These help paint a clearer picture of who we are and what we’re capable of, both internally and externally.”

Fundamental research

Van Hest emphasizes that fundamental research has an important place within the institute. “Chemistry is so broadly applicable, there’s not just one holy grail where we pour all our efforts into,” he says. “Molecules are the building blocks of matter; everything is made up of these tiny particles. You want to understand how those building blocks work together, creating materials with certain properties. That’s the basis which you can use in designing smart coatings or materials that enable tissue repair. There are lots of possible application areas, but all of them build on that foundation.”

Even so, fundamental knowledge is often a neglected part of scientific research, according to Meijer. “It also has to do with how journalists communicate about science. They’re often not that interested in very fundamental knowledge that's difficult to explain. A new application that everyone understands sounds much more appealing. There is always a lot of attention for innovations, but hardly any for fundamental knowledge. Even though everything is based on it.” He says that one of the institute’s important tasks is to give fundamental research the appreciation it deserves but often doesn’t receive elsewhere. “Here we say: ‘we do think that's very valuable'.”

"There is always a lot of attention for innovations, but hardly any for fundamental knowledge. Even though everything is based on it."

One of the fundamental questions is how to give molecules certain properties. “A molecule has no properties of its own, it acquires them by interacting with other molecules. It’s somewhat similar to how people are defined by their interaction with other people and how they relate to each other within a community,” Van Hest explains. “The more building blocks you bring together, the more complicated it gets. We’re focusing on the foundation now; how to give the molecules new, important properties.” This knowledge can be applied in many areas: from the energy transition to the development of recyclable materials to solving health problems. “You can’t achieve substantial breakthroughs until you understand that foundation, which is how molecules work together,” he stresses.

"You can’t achieve substantial breakthroughs until you understand that foundation, which is how molecules work together."

Making science visible

“I think it was a great idea of Bert to set up the Animation Studio right away,” he continues. The animation videos that visualize complex molecular systems can be found on the ICMS’ YouTube channel. Koen Pieterse, the studio’s team leader, has a PhD in molecular research himself and works with colleagues with a background in design. “Together they see to it that something abstract, which is difficult to comprehend, is translated into something visible. It’s been incredibly helpful in increasing public understanding of what we do here,” Van Hest says.

“Molecules are complicated structures,” Meijer explains. “When they’re small, it’s easy to understand the dynamics of the molecule. But when they’re larger, say a piece of protein or DNA, the question becomes: what does the structure look like at one specific point in time, one nanosecond later and two nanoseconds later. Because there’s constant movement.” People have a hard time understanding complex things in motion, but the videos allow them to better understand the dynamics, he believes. “Many questions in the field of health and materials development have to do with the lack of understanding of the structure of molecules in place and time, for example, how pieces of DNA are replicated and how this results in a protein. It’s difficult to explain in words, but a video allows you to illustrate it much more accurately.”

Duplo building

When asked what he is most proud of, Van Hest responds without hesitation: “Of the fact that we’ve always been able to create an environment in which people excel. We’re here for the people, so that they can develop their career to the best of their ability.”Meijer agrees. “ICMS are just four letters. It’s nothing. We’re here to support people in doing what they want to do. It’s not about the institute becoming highly successful, but about the people becoming successful.”

And that is working out quite well, given that the researchers affiliated with the ICMS are racking up one award after another. For example, Patricia Dankers, professor of Biomedical Materials and Chemistry, received a Vici grant this year, which she plans to use to create an artificial version of the material that surrounds cells in the human body. Sandra Loerakker, associate professor at the Department of Biomedical Engineering, received a Vidi grant last year. Loerakker is developing computational models to understand and predict heart valve regeneration. In 2020, Van Hest himself, whose research includes developing artificial cells and nanomedicines, received the Spinoza Prize, the most prestigious award in Dutch science.

Still, Van Hest and Meijer would rather not talk about individual successes. “If you put the spotlight on a single person, you’re selling four others short,” Van Hest thinks. “That’s not our style,” Meijer confirms. He himself sees the institute “as a duplo building.” Meijer: “It’s a continuous process in which you build something beautiful together, and every building block is equally important. It’s not like two building blocks make all the difference and turn the building into something beautiful. Every little contribution plays a role.”

The role of ICMS itself also should not be overestimated, thinks Meijer. “When someone wins an award, there is sometimes a lot of focus on the institute itself, as if that’s the most important thing, but it’s not. Those people also work at their department and collaborate with people who are not part of the institute. So it’s never just due to the ICMS, which only ever plays a minor role.”

Healthy competition

One of the secrets to the institute’s great success, according to Van Hest, is the strong sense of collegiality and the fact that people support each other. “There is so much goodwill here. If your colleague is successful, it reflects positively on the entire institute. It stimulates the community and brings a positive energy to the whole organization.”

“At ICMS, everyone receives a tremendous amount of support and appreciation, but there’s also healthy competition,” adds Meijer. “If Jan and his group achieve something great, I congratulate him of course, but I also think to myself: ‘dammit, time to step up our game’,” he says, demonstratively banging a fist on the table. “It may not be a very modern thing to say, but I firmly believe you need that feeling to get ahead.” Van Hest nods in agreement. “Take tennis, for example. I think Djokovic and Nadal have been so successful for so long because they are always in friendly competition with each other. They both want to be the best and so they keep challenging each other. The same thing happens in science.”

"We have one simple objective: to support people who are involved in the institute in their wish to work with others as best we can."

Another thing that makes the ICMS so unique is its steadfastness, Meijer believes. “You choose to do something and you stick to it. Other institutes are too quick to get swept up in something new.” According to him, a clear long-term vision is key. “We have one simple objective: to support people who are involved in the institute in their wish to work with others as best we can.” That makes it very easy to determine the strategy and make choices. “If something is not in line with this, you don’t do it.” It is this clear direction, among other things, that has allowed the institute to be successful at its job of supporting people for so long, he believes.

Knowing when to stop

There is plenty of scientific research to be done in the coming years. The new Interactive Polymeric Materials Research Center received more than 15 million euros from the Gravitation Program, a grant program run by NWO, to develop new dynamic and sustainable polymer materials. “These are materials that adapt to the user’s needs,” Van Hest explains. “You can use them as coatings that can filter daylight, generate energy or increase or decrease friction. Or materials that are so cleverly constructed that they can be broken down piece by piece like Lego bricks after use, so that you can convert them into new materials. That’s one of the many themes we’re working on; one we have committed ourselves to with the program for the next ten years.”

Having served five years in the role of scientific director, Van Hest is about halfway through his tenure. Like Meijer, he plans to hand over the directorship to a successor after ten years. “I don’t think it’s wise to continue for longer than that. Eventually, you get stuck in a rut, you lose your innovative power and don’t see things clearly anymore. Fortunately, I know enough great people within the organization who would be able to take over and revitalize things.”

That said, Van Hest says it is not a given that the ICMS will still exist in 5, 10 or 15 years. “We don't focus on how to keep the institute alive, but on how we can most effectively help people. You don’t necessarily have to continue indefinitely.” According to him, the institute should only continue to exist for as long as it adds value. “Maybe there will be changes in the university’s structure in the future, with the result that other places will take over our role. In that case, the ICMS would no longer be needed.” If you’ve made yourself redundant as an institute, it’s best to stop, he believes. “This can also be a positive thing, for that matter, because it means that the scientists know how to find each other without our help.”

Source: Cursor.

Media contact

More on Health

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](https://assets.w3.tue.nl/w/fileadmin/_processed_/e/9/csm_BvOF%20sluitstuk%20Luuk%20van%20Laake%203_c4df17db41.jpg)

Latest news