MantiSpectra: Seeing more with invisible light

The TU/e spin-off MantiSpectra is striving to develop tiny chips that can monitor crops before harvest and help sort materials for recycling.

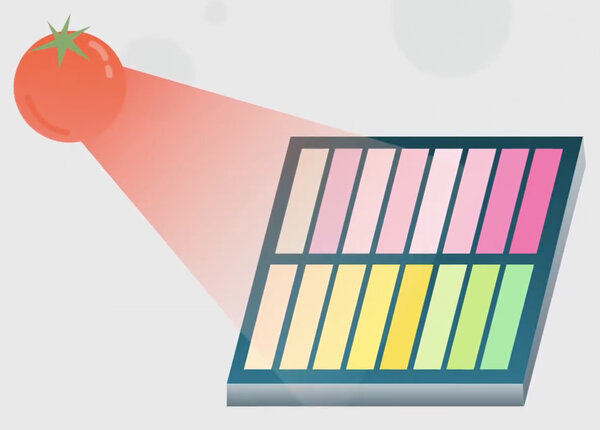

Our world would be lost without light. The human eye detects visible light which allows us to see the color and size of objects. But invisible light, like infrared radiation, that our eyes can’t see and is emitted by food, drugs, and other materials, can be filled with hidden information on chemical composition. Possessing the super-vision to detect this light would therefore prove invaluable in many industries such as the agri-food sector. MantiSpectra – a TU/e spin-off company – is developing innovative spectral sensing devices to measure and decode these invisible light signals.

Spectrometers collect light, break it apart, and tease valuable information from it. Here, “light” could be the visible light our eyes detect or invisible electromagnetic waves like infrared radiation, which is used in optical communications and also produced by chemical reactions in crops and in stars like our Sun.

TU/e researchers Maurangelo Petruzzella, Francesco Pagliano, and Andrea Fiore know a thing or two about collecting light and analyzing it with spectrometers. Back in 2017, they co-authored a Nature Communications paper that proposed a way to build a micro-spectrometer that could fit in a smartphone, research that caught the eye of the Dutch national paper de Volkskrant.

“The response to the micro-spectrometer work was extraordinary,” recalls Andrea Fiore, professor in the Department of Applied Physics. “To see it featured in de Volkskrant was a major vindication for our work to say the least!”

Petruzzella – formerly a researcher in the department of Applied Physics and now CEO of MantiSpectra – also has fond memories of that paper: “We saw the potential, and the wider public saw the potential. But we knew we needed to change the technological approach for it to be truly suitable for everyday application. We needed something that was much simpler and more robust.”

And so, began the journey towards the TU/e spin-off company MantiSpectra.

From postdoctoral beginnings

After completing his PhD cum laude in 2017, Petruzzella moved into the world of postdoctoral research with a focus on the design and fabrication of spectral sensors to analyze light from various sources.

“What we have now with MantiSpectra comes from the efforts of our research team during my postdoctoral endeavors,” says Petruzzella.

But while MantiSpectra has evolved from fundamental research, it still took some time before the research led to technologies that could be used in society. “It wasn’t like we had picked out the company name before we started,” explains Petruzzella. “It’s been an organic process, and MantiSpectra has been an organic outcome.”

MantiSpectra is seeking to advance technologies in the field of miniaturized and portable spectroscopy, in particular by advancing a spectral sensing chip inspired by research from Fiore’s group. “It’s interesting when I think back to the start. We had this new technology, but we didn’t have a particular application in mind,” notes Fiore. “When we started to better understand the potential applications in the agri-food and pharmaceutical industries, it became clear what was really needed to make a simple, yet useful sensor.”

What’s in a name?

So where does the name MantiSpectra come from? Well, there’s an interesting animal kingdom link to the field of spectral sensing as Maurangelo Petruzzella explains.

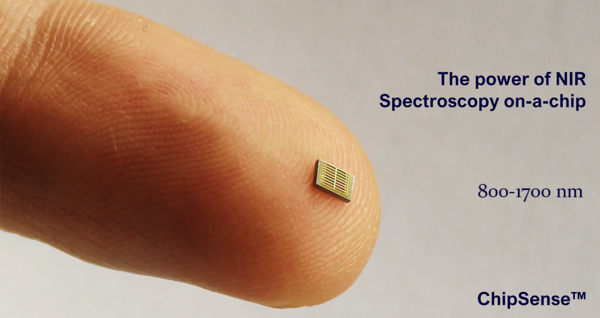

“The retina of the human eye is home to photoreceptor cells that detect light. There are two types, rods for dim light conditions and cones for bright light. We have three different cone cells, each sensitive to different wavelengths of light – red, green, and blue. But the Mantis shrimp easily trumps the human eye as its eyes can have up to sixteen different photoreceptor cells, with each one sensitive to a different wavelength of light between ultraviolet and infrared.”

It’s the replication of this ‘super-vision’ of the Mantis shrimp that forms the basis of MantiSpectra’s technologies, hence the name that honors the sea-dwelling creature. “Obviously we’re not trying to replicate the eye of the Mantis shrimp, but our sensors use a similar principle of measuring different parts of the spectrum using different receptors,” says Petruzzella

Organic applications

MantiSpectra are specifically interested in the range of wavelengths in the near-infrared (IR) part of the electromagnetic spectrum, between 900 and 1,700 nm. “This range of wavelengths is of particular interest for spectral sensing applications involving organic materials. This range of wavelengths is associated with absorption bands in chemical bonds like O-H (oxygen-hydrogen), C-H (carbon-hydrogen), and N-H (nitrogen-hydrogen),” says Petruzzella.

“The visible spectrum provides some information but measuring at near-infrared wavelengths gives far more information for many important problems, and this can be used to better characterize organic and inorganic substances in agri-food and healthcare,” adds Fiore.

MantiSpectra’s approximation of the Mantis shrimp’s eye is a chip, roughly 1 millimeter by 1 millimeter, that’s home to sixteen electronic photoreceptors or pixels, each sensitive to a different range of wavelengths in the near-IR. Despite its tiny size, the chip’s sensors open up a world of possibilities, particularly when it comes to monitoring the freshness of fruit and vegetables before harvesting.

When is the right time to harvest?

“Identifying the best time to harvest fruit and vegetables can be difficult for farmers. They can rely on years of experience and go with instinct, but things can go wrong. If picked too early, the produce may not have reached its maximum taste, if picked too late then the produce may be spoilt. Our sensor could really help farmers in the future,” says Petruzzella.

Sometimes fruits or vegetables may not look like they are ready to be harvested, but a giveaway indicator of their ripeness can be found at near-IR wavelengths. “Our eyes might not be able to see these wavelengths, but they can be measured with our pixel sensor,” says Fiore.

It’s this hidden data that MantiSpectra’s chip exploits, but before the system can give a proper recommendation as to when is a good time to harvest, the system needs to be trained using machine learning approaches.

“Before using the chip in fields, it must be calibrated. The data collected by the chip is analyzed with an algorithm, but this algorithm needs to be trained, and that’s where machine learning comes into play,” points out Petruzzella. “We use a training data set that comes from a crop of interest. Different products, or in some cases different varieties of a product, may need separate training – this is what we are testing for the different application cases”. The same approach can be used to train the sensor system to classify different types of plastics or fabrics, which has great potential applications for recycling.

Exciting adventures to come

It goes without saying that exciting times lie ahead for MantiSpectra, and 2021 promises to be an adventure for the startup, founded in October by Petruzzella, Fiore, their colleague Francesco Pagliano, and TU/e Holding. Things started fantastically in 2021 when MantiSpectra was mentioned by name in one of the year’s first press releases from the Dutch government.

In addition, MantiSpectra has received considerable support from PhotonDelta, as well as from Innovation Industries, NWO, and the Metropolitan Region Eindhoven. And the MantiSpectra team is growing, with several additions to the MantiSpectra team.

“We are only at the beginning, but we know that there is so much potential for this technology, whether it’s monitoring crops, classifying materials for recycling, or checking on the chemical composition of drugs. The future promises to be exciting,” says Petruzzella.

Andrea Fiore also echoes the enthusiasm of Maurangelo Petruzzella: “In the early phases of the technology, we were looking for an application. Now we are spoilt for choice, it’s hard not to be enthusiastic.”

From initial research at TU/e, MantiSpectra was born, and looks set to play a key role in the utilization of spectral sensing technologies in our daily lives. They are only at the start, but MantiSpectra’s super-vision technologies will help us to see things that we would otherwise miss completely.

The superpower of near-IR vision has arrived!

Find out more about MantiSpectra in an article by Bits&Chips from December 2020.